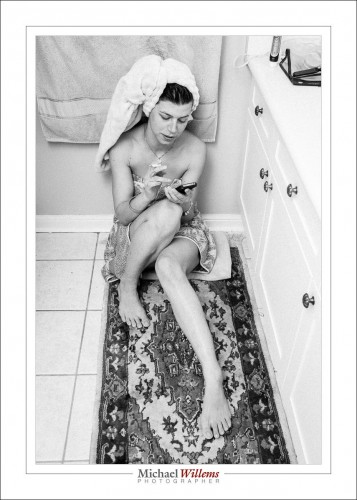

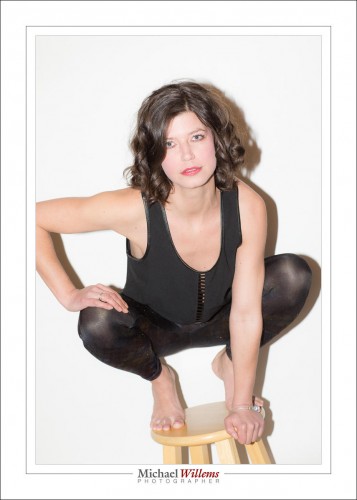

Today, another example of the “Amateur Aesthetic” or “Snapshot Aesthetic”made popular by such contemporary photographers as Terry Richardson, after Diane Arbus and Nan Goldin, two of my favourites.

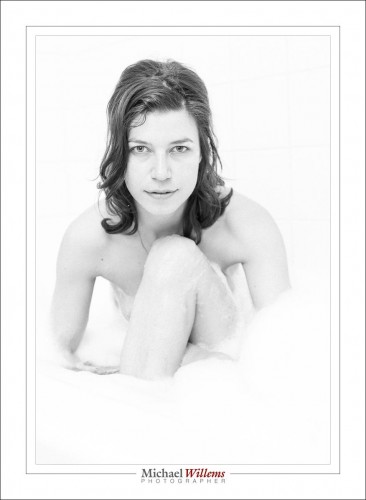

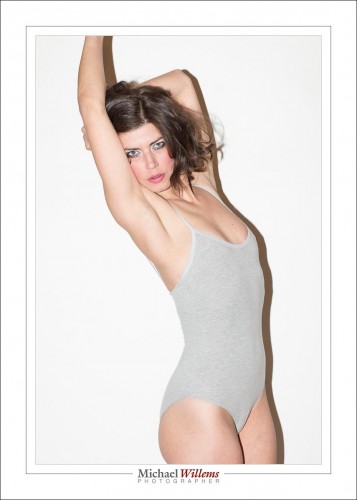

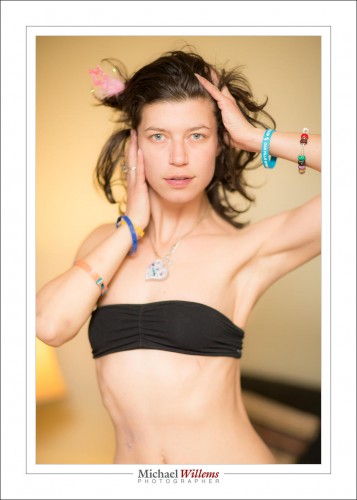

Here’s mine, a high-key model shot:

We call it amateur, or snapshot, because you use a flash straight on, and aim at the subject, and have the subject stand in front of a white backdrop, camera aware. Like Uncle Fred does. This gives you the drop shadow. It also, however, gives you very flattening light, and models like this: it hides any facial features. Overexposing a little, or rather, exposing brightly, makes it even better in that regard.

Unlike your Uncle Fred, my models and I think carefully about composition, light, and expression and pose. The direct flash means you need to aim the subject’s face down a little, else light comes “from below”, which is never flattering.

So nothing is left to accident, in spite of the amateur look.

For this shot, I used 1/160th sec, 400 ISO, f/5.6 and an on-camera 600EX flash. The flash compensation, like in the examples of a few days ago, was set to +2 stops, and I used TTL flash metering for flexibility.

Your assignment for today: shoot a portrait like this. I am about to teach a TTL flash course, and my student will do this as well. In addition to “proper” flash, you need to know techniques like this as just another tool in your toolbox.