You have an iPhone or similar? Then do this: in every location you shoot, take an iPhone shot first. Because iPhones have GPS coordinates built in.

First add all pictures to a collection. Go to that collection. Select all pictures.

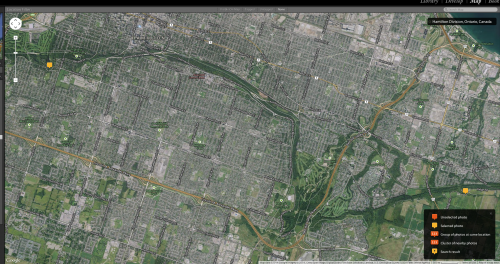

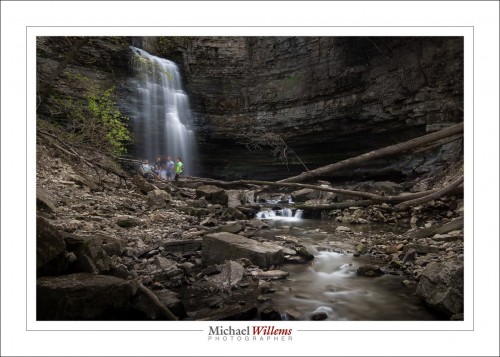

Now go to the Maps module. You see the locations show up. But look at the numbers: you see only the iPhone shots show up, like this, of the two locations I shot waterfalls at, the other day (the yellow dots top left and bottom right, and both say “1”, meaning “in what you have selected, there is 1 shot at this location”):

Now in grid view, select all the shots you took at the first location They all show as selected. Then click once on the JPG shot: it shows as more brightly selectd.

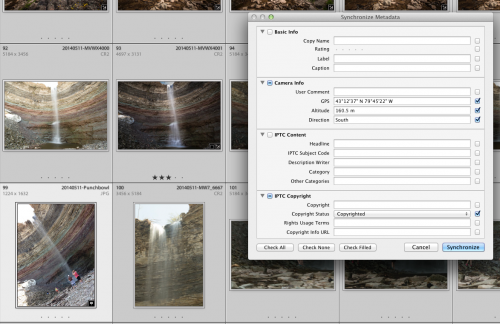

Now you can, from the METADATA option in the menu, select “Synchronize Metadata…”:

And if, as here, you “super-selected” the iPhone shot, which has GPS data, the GPS and altitude fields are filled in. Now turn on the tickmarks as I have done, and when you click “Synchronize”, these fields will be synchronized to all the other photos in that location.

Now repeat that for the next locations: select them, super-select their iPhone shot, and sync.

Now the numbers show the actual numbers, i.e. all photos now have locations built in:

A simple, effective way of getting GPS data into your pictures even if your camera does not have built-in GPS.

Cool, or what? Yes, Lightroom is full of such tricks. And so am I.