I am back from Aruba (the roundabout way, via Caracas, Bogota, and back via Panama City, Orlando) and I am blogging again. About, of course, travel photography; what else.

When I shoot some pictures (an this was not a picture trip: rather, a vacation with some pictures), I think “what is the character of the place”. So I think, when I think of Aruba, things like “the trip”. I will spare you all the photos, but it is important to get these “B-roll” photos: the ones that tie together the photos of the trip. Travel Photography is storytelling.

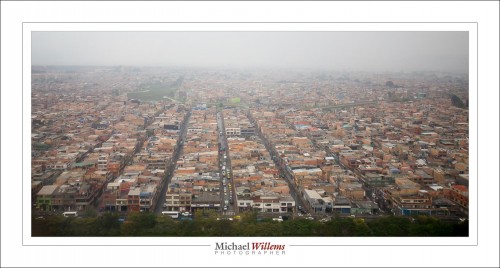

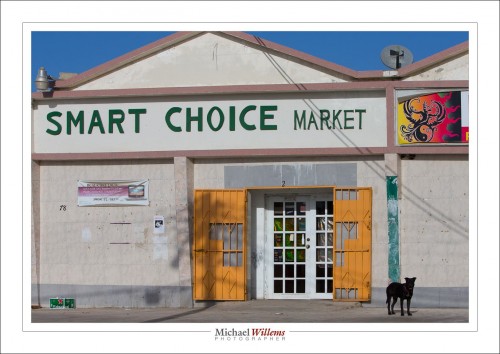

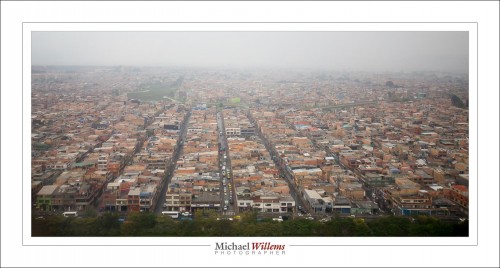

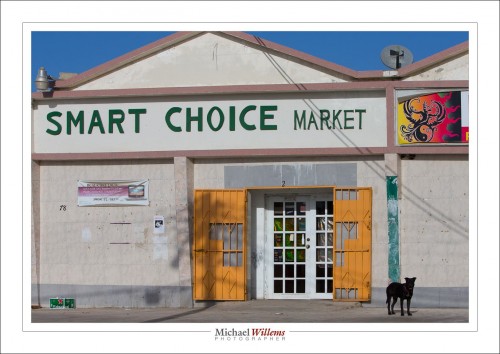

So you include shots like this, of Bogota, Colombia, by the airport (I travelled to Aruba via Caracas and Bogota):

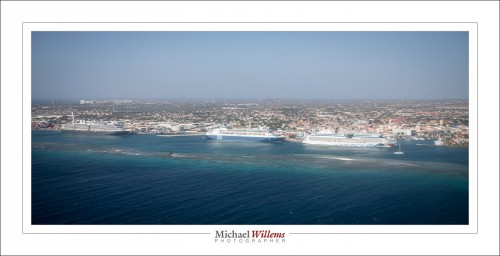

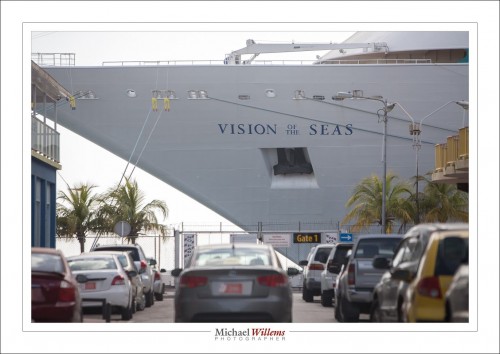

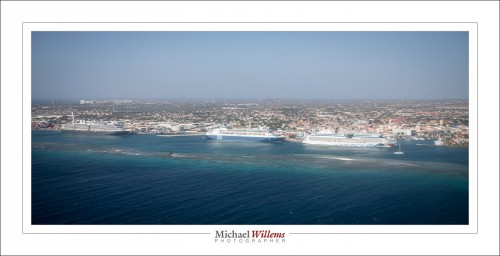

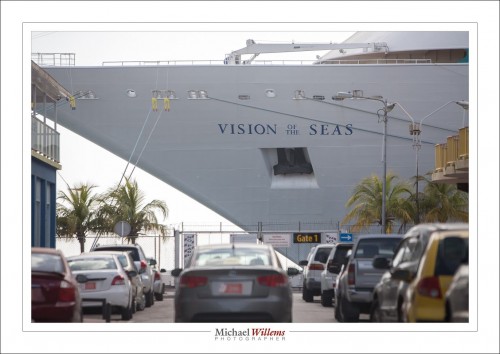

And of Aruba arrival:

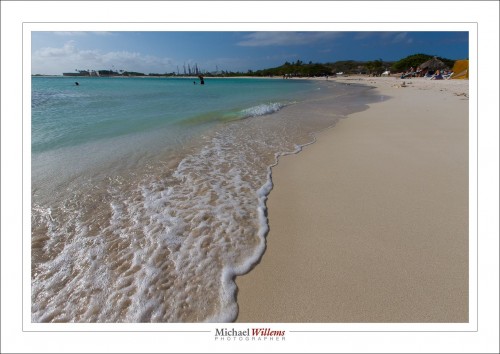

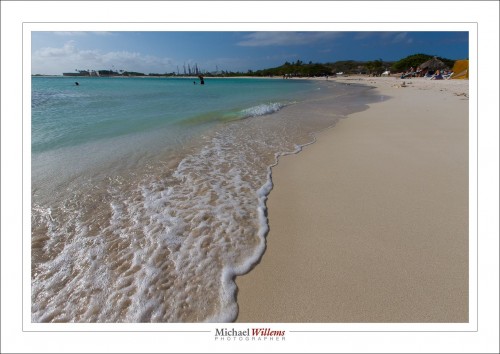

When I get to my destination, I think “beach”:

..and I think “sites”: the lighthouse…

Oranjestad…

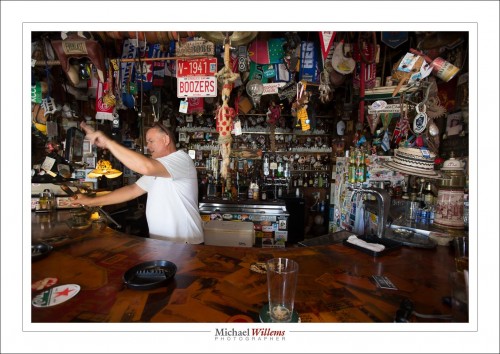

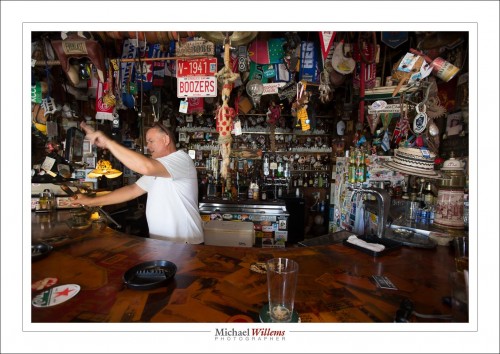

Charlie’s Bar, San Nicolas:

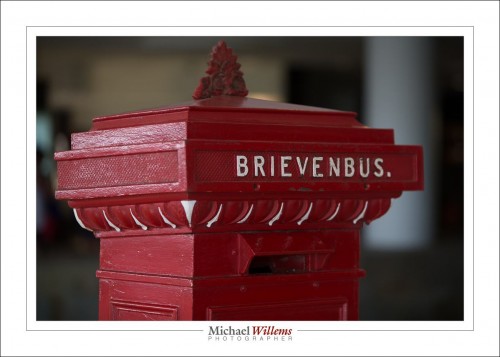

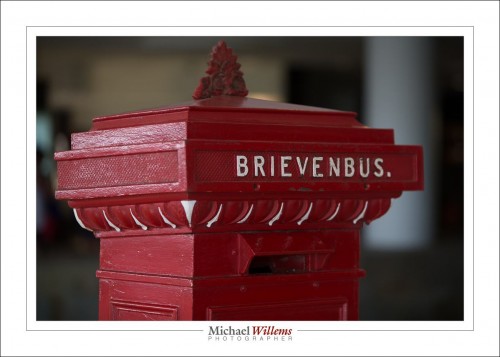

Dutch heritage:

The way ordinary people live:

And yes, of course I do also think of sunsets:

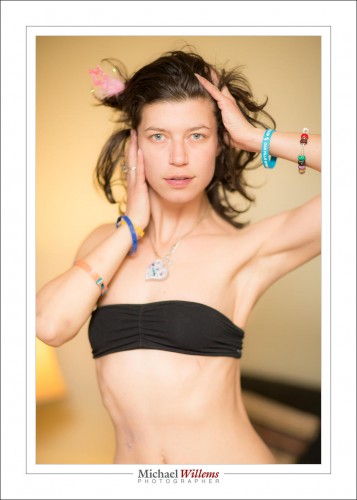

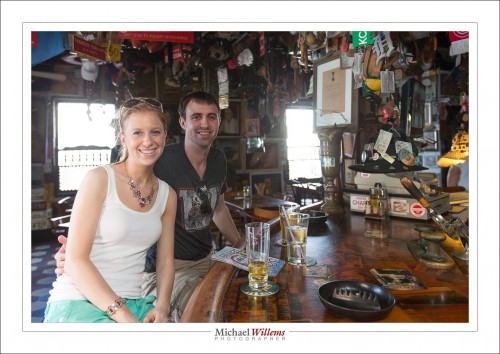

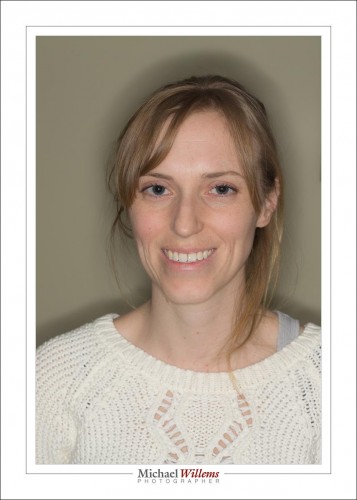

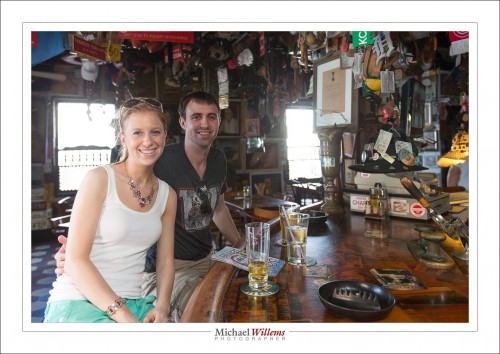

And one more thing—I am always happy to offer the people I meet a memory, as well. Like the young couple in Charlie’s Bar:

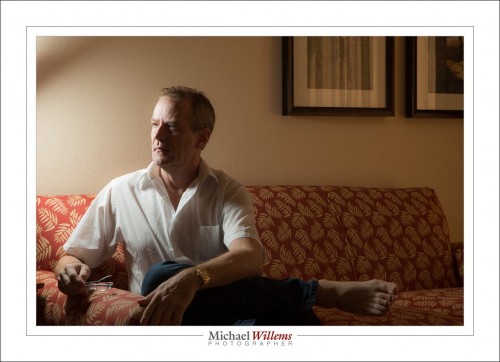

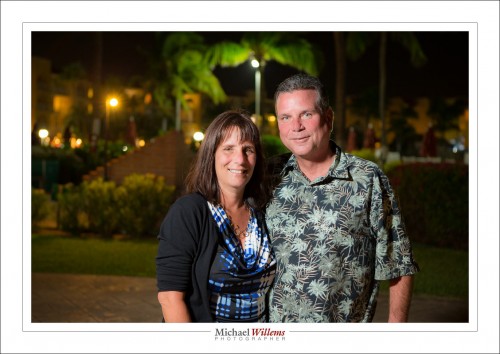

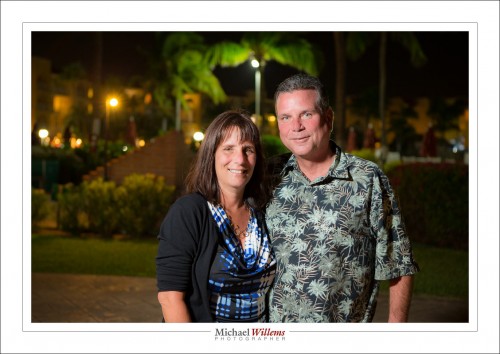

And the couple next door:

…I mean, why not? They can’t take photos like this, so I’ll do it for them. A very small effort, but it does require some equipment (bounced flash in the first one; off-camera flash with a Honlphoto softbox in the second one).

More about this trip, and in particular about its photography, in the future, but now to unpack my stuff. A week of 31C, now followed by freezing again. But the photos last, and that of course is why we like to take them.