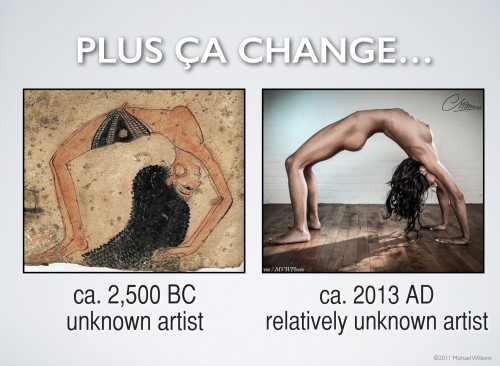

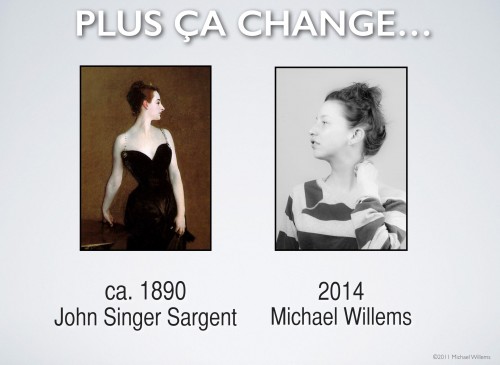

Evan Spiegel, the CEO of Snapchat, said the other day that “photos used to be about preserving memories, but now they are about communicating”.

And while I am not sure I agree with that entirely, he is right that things are changing. The trends are clear:

- Everyone has a cellphone camera.

- These are getting better. While they will never equal a DSLR, they are good enough for sharing on the web.

- And that is what happens: iPhones and instant sharing apps have changed the way photos are seen.

That means a few things. First, it does mean that at least initially, photos are about the “now” rather than about the past. Utilitarian photos. You send your spouse a photo of the three types of olive oil on the supermarket shelf so she can tell you which one.

It also means the quality goes down. It’s not about technical perfection if you are just asking a question, making a point, or choosing olive oil. It’s not art, it’s just talking.

And yet. People do still appreciate beautiful photos. And after the talking and “living in the now” is over, you remember the past. It’s not an “either/or”; it’s an “and-and”.

Not art, but a driveway crack

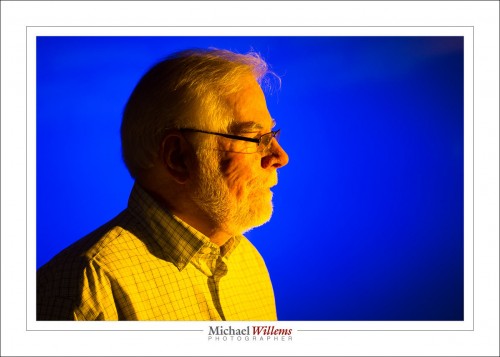

Take me. I make iPhone pictures all day. They are utilitarian, for the moment, communicating. Like the one above, to show a crack in my driveway asphalt caused by leaking car fluids. But I also do this:

(16-35mm f/2,8 lens, at 16mm). So the need for a good camera still exists. You need a “real” camera when you:

- Need a blurry background.

- Need a wide angle lens.

- Need a telephoto lens.

- Need quality prints.

- Need large prints.

- Want to shoot in the dark.

- Need to capture motion.

- Need repeated (“continuous drive”) photos.

- Want to use flash (whether “creative” or “technical”).

…and so on. The list is long: many reasons to own not just a cell phone, but a quality DSLR as well.

Photography is changing, but it is a good thing, in this case. Nothing is being taken away; we are adding. Snapshots for the “now”, using your cell phone, and reserving memories with the DSLR. A win for everyone concerned.

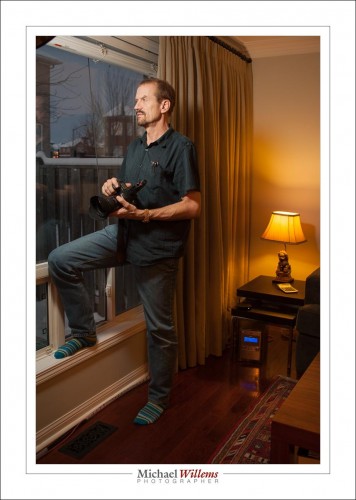

So take lots pf pictures and enjoy. And do not forget to bring your cell phone and use it. Here, let me start. What I am looking at (or would be if I turned upside down):

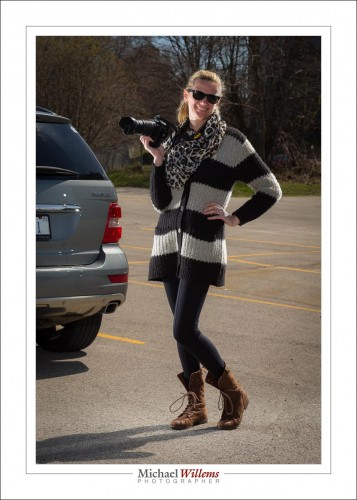

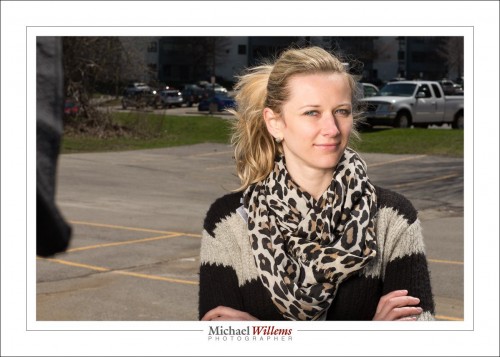

..and what I see next to me (Awww…):

Quick and easy. Snap, upload.

But remember, the same basic rules apply in both cases, so learn composition, learn how to change the photo’s exposure on the iPhone, learn the effect of distance, and so on.

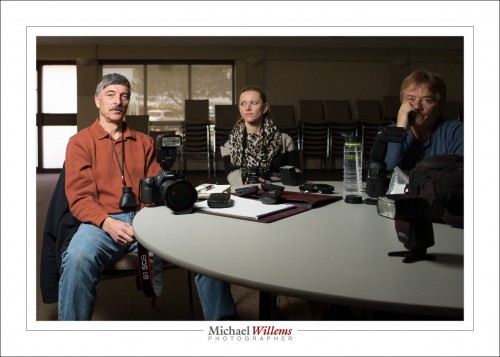

(Quick test question: what change did I need to make before the final ‘click’ to the exposure of the above photo: up or down, and why?)