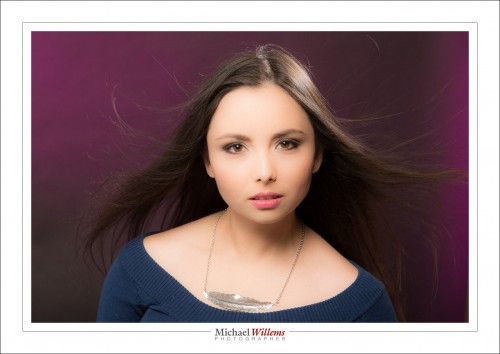

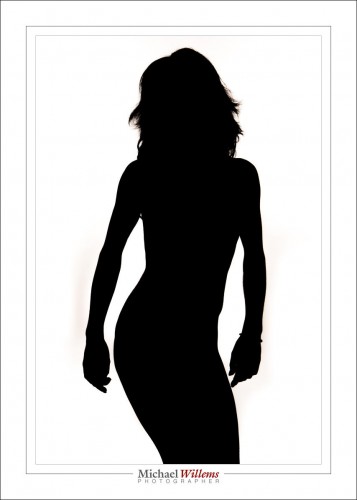

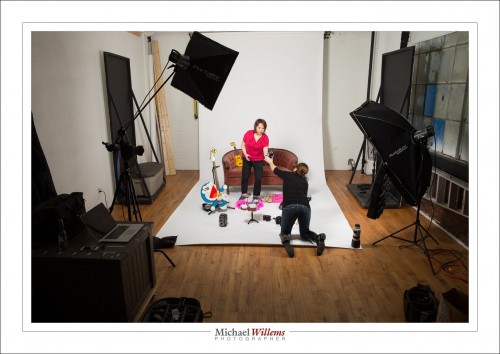

A simple trick, used by photographers the world over, is this. Can you see what we did in this shot from two days ago, a portrait of Liz Medori?

Yup, we used a fan. A simple cheap fan; I usually use an industrial fan from a home supplies store. That fan makes the hair do its wild sexiness thing, which you will see in many model photos.

And the good news: You need to know no technique for this. Even if you are a total beginner, nothing stops you from aiming a fan at your long-haired subject.

What else did I do in that photo? We had a make-up artist, Melissa T. We lit the model with one overhead softbox straight in front of her, plus one hair light aimed at us, for shampooey goodness™, plus one background light with a purplish gel aimed at the background. And I shot with a 70-200mm lens at the typical studio setting of 200 ISO, 1/125th second, f/8.

But even if you do not know what that means; go for it with the fan!

___

NOTE: As usual, this content is brought to you free of charge. As are all the other blog posts (the entire four-year searchable archive); the articles; and things like the free book chapter from my latest book – the entire chapter on Exposure (go to http://www.michaelwillems.ca/e-Books.html and click on “download sample). Yes, in addition I sell e-books and training and photography sessions, but this content is provided free of charge.

Since this is a business, though, let me ask you to so something in return: please send this post to three friends who may be interested. That way even more people benefit from this advice and these free lessons.

Fair deal?