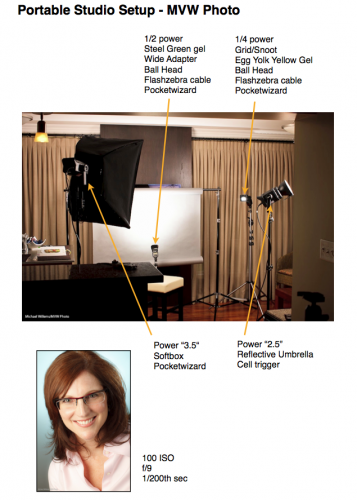

Studio shooting is very simple. This, today at my Vistek flash course, took but a moment or two to set up: a studio, using just ordinary speedlights and a few accessories:

Two speedlights, fired by pocketwizards. One on a lightstand, through an umbrella. The other on a clamp through a snoot from the back. Both were to manual power at 1/4 power.

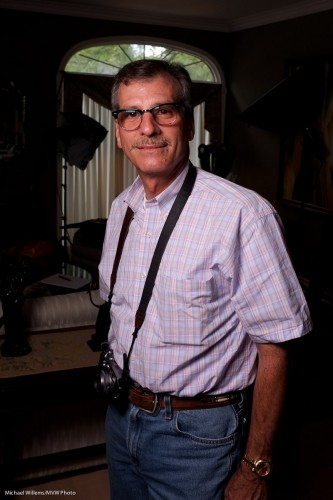

And at 200 ISO, f/5.6, 1/125th second, that results in this student portrait:

And the great thing about this kind of “manual” shooting, where the flash is also set to manual (rather than using TTL metering) is that once you have the light right, it is right for every subsequent shot.

Regardless of subject: a pale person dressed in white, darker person dressed in black, and everything in between. You will never need to re-meter, provided you have each subject stand in the same place.

And how do you like those smiles? And a hint: they were not created by telling people to smile.

___

NB: This post shows you it’s simple. Want to learn the details of this type of studio portraiture? Come to my Tuesday evening course in Hamilton: http://www.cameratraining.ca/Studio-Ham.html and I’ll teach you all this – pocketwizards, light meters, light angles, and more.