A Neutral Density (ND) filter is useful when you want to cut light. Why would you want to do that? Because

- You may sometimes want to create longer exposure times, and cutting light may be the only way to do it.

- Or because on a bright day you want a larger aperture, in order to get more selective depth of field.

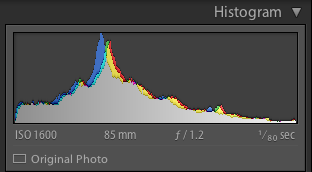

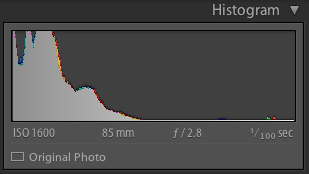

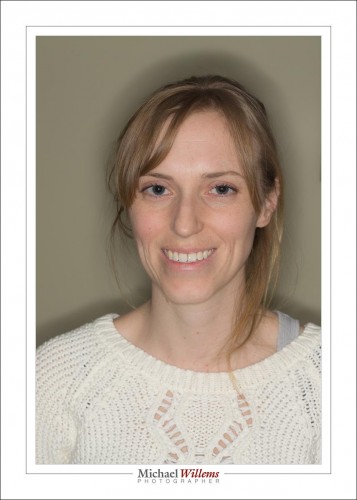

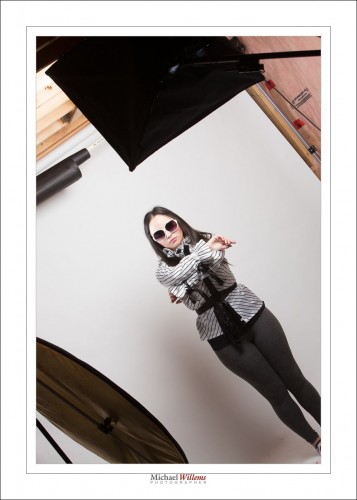

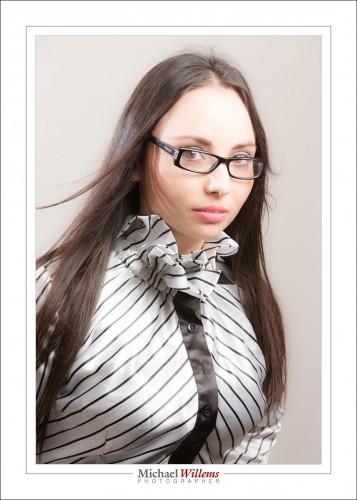

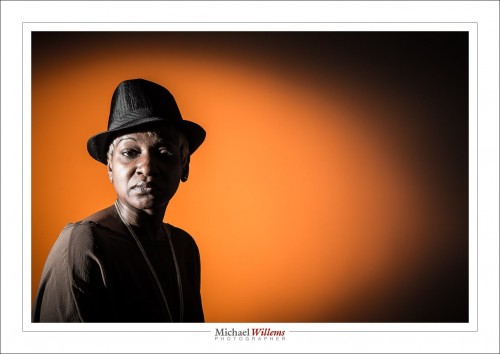

Imagine you have this:

At low ISO (100) and high f-number (16) that was 1/4 second (using a tripod, of course). I used my wide angle 16-35mm lens.

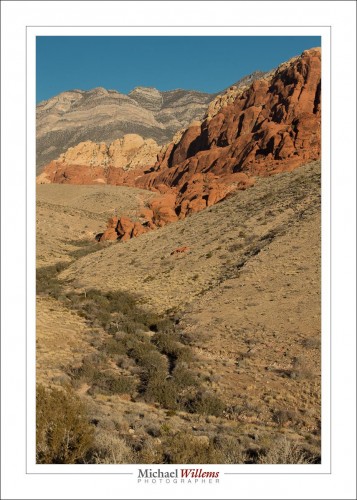

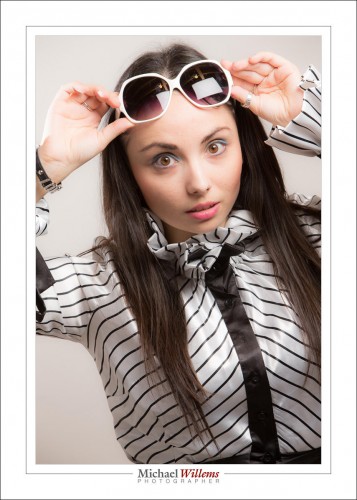

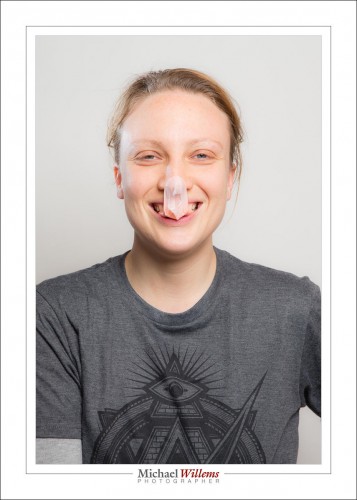

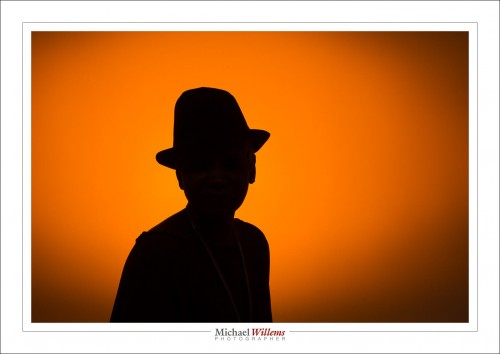

But what if I wanted a slower shutter speed than 1.4 second? For instance to make a river or a waterfall look all smooth? I cannot lower the ISO or increase the f-number (at least on this lens), so I need a trick. And that trick is the ND filter. It evenly cuts light, so then you need a faster shutter. Like here, the same shot with an ND filter:

But it looks just as bright?

Yes, because at the same time as cutting the light, I set the shutter speed to a much longer time, namely one of 5 seconds (set manually and metered by trial and error as much as by the meter, which is less accurate under these circumstances). Anyway, 5 seconds is 20 times less light than 1/4 second (since 5 sec/0.25 sec = 20). How many stops is that? It is 4.32 (roughly 4 and a third) stops less light, since 24.32 = 20. Um, high schoolers and above: you can calculate this number of 4.32 as follows:

- 2x = 20 (base 2, since a stop is halving or doubling the light)

- x = log2(20)

- x = log(20)/log(2)

- x = 1.301/0.301

- x = 4.32

So my ND filter gave me 4.3 stops less light.

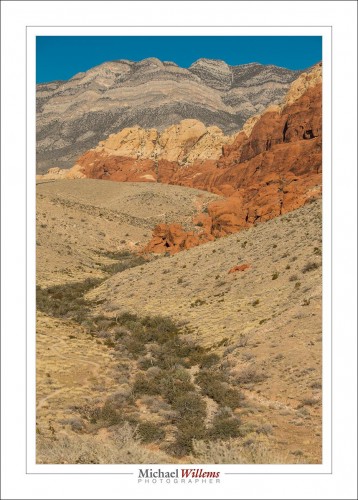

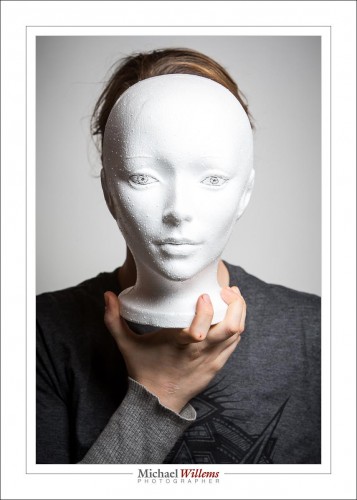

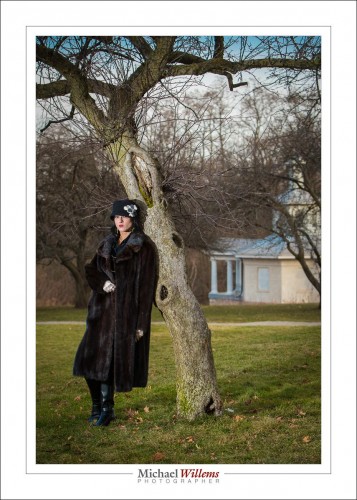

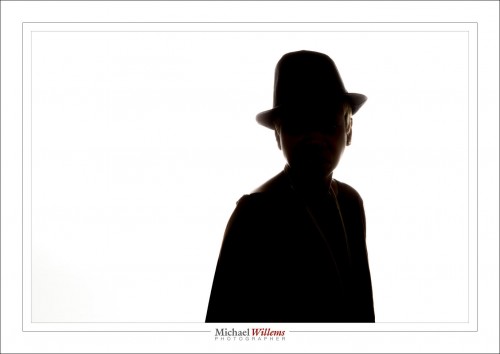

I used an 82mm Cokin variable density ND filter. One where you turn the filter to make it darker or brighter. Turn it one way and it cuts 1 stop; turn it the other way and it cuts 8 stops, says Cokin. I call “no” on that. Even at the darkest, it is not that dark, and in any case, when I am zoomed out and then go beyond 4-5 stops, this happens: (made one stop darker, i.e. 5.3 stops, now using a shutter speed of 10 seconds)

See how bottom left to top right it gets all weirdly dark? Not usable, so this filter is not really usable much beyond 4 stops with a wide angle lens.

An cheaper Cameron filter was even worse when turned all the way to the “max” mark for “dark”:

All variable filters do this as far as I know, since it is due to physics; but some are worse than others. To avoid it, zoom in, not out, and then look through your viewfinder to see when this problem happens, and back off from there.

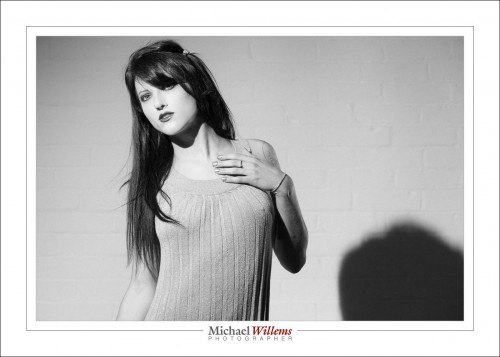

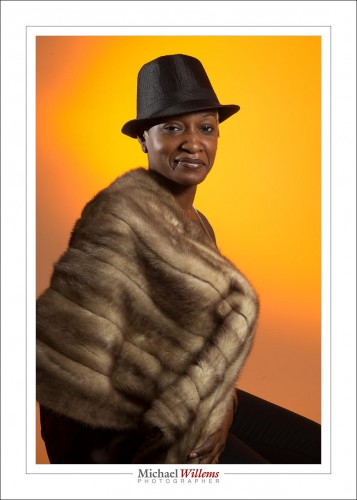

Another thing to watch out for is flare. The cheap filter did this, look at the bags on the top right:

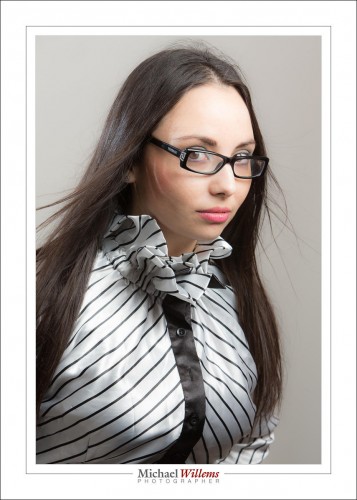

And the better Cokin filter:

Not perfect, but better.

So you now know why to use neutral density filters; how to use them; and the possible pitfalls, including what to watch out for if you buy the variable variety. You may just want to get a non-variable 5x or 8x ND filter.

And you’re welcome.